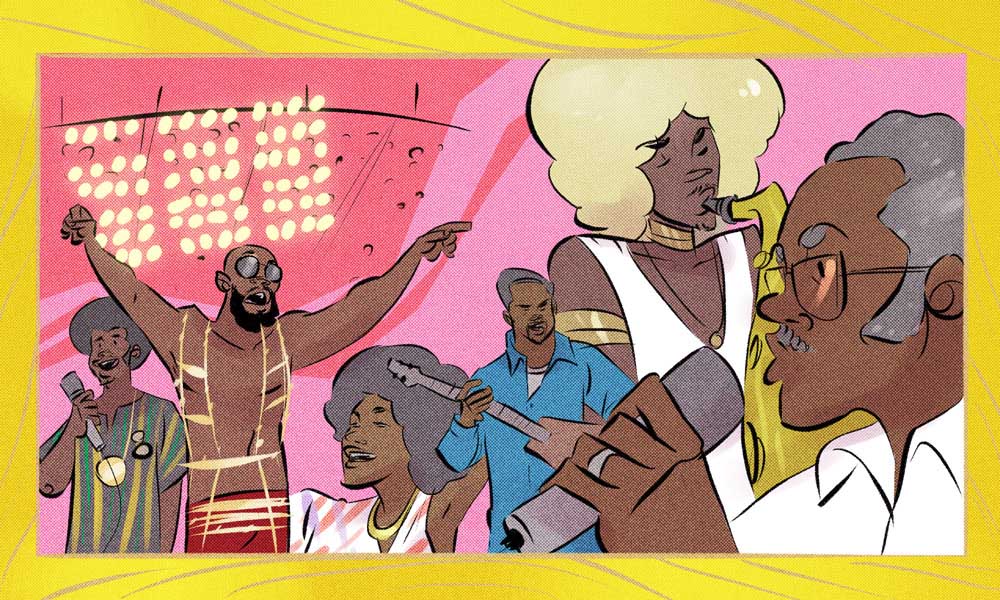

On one sweltering hot August day in 1972, a sea of Black folks filled Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for one of the greatest concert events of the era. The Wattstax concert remains a cultural touchstone, a moment when Blackness sought to heal itself by celebrating itself.

Experience the Wattstax concert.

The Wattstax concert was more than soul’s Woodstock, it was a snapshot of the Black-is-Beautiful movement in full bloom; an early 70s salve for the wounds caused by the struggles of the 60s and the hardship of Vietnam, which birthed a sense of solidarity and celebration within a community and culture. The historic show was born of the Watts Summer Festival, which had begun in 1966, a year after the Watts Riots, to showcase the community’s vibrant art and music. African art, a parade, and a beauty contest were centerpieces of the annual event, with luminaries from Hugh Masekela to Muhammad Ali taking part in the late 60s.

Stax Records, dubbed “Soulsville” as an intentional counter to Motown’s “Hitsville” moniker, championed itself as a label with its ear to the street. By the early 1970s, there was no Blacker label topping the charts than Al Bell’s Memphis imprint. Stax saw an opportunity in partnering with the Watts Summer Festival to both create a Black showcase, and garner great publicity for a label that championed Blackness, donating all profits going to community charities.

The event also gave Stax a chance to highlight a roster that had gone through a period of flux at the dawn of the 1970s. Stax famously lost Otis Redding and most of the original Bar-Kays in a tragic plane accident in 1967, and label superstars Sam & Dave (of “Soul Man” fame) moved to Atlantic Records a year later. To mitigate the losses, Bell had spearheaded a surge in releases from mainstay Isaac Hayes, as well as new stars like the Temprees and the Soul Children, the now-refurbished Bar-Kays, and the legendary Staple Singers, who’d joined Stax in 1968. These were projects meant to bolster and re-establish the label’s standing. Bell looked at the Wattstax concert as a great way to cement the label’s new voices.

The Wattstax Concert

Singer Kim Weston (ironically, a Motown alumnus) opened the event with a soulful rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner,” followed by a young Rev. Jesse Jackson, the event’s official MC, delivered his rousing and soon-to-be signature “I Am Somebody” speech. Weston then led a cadre of Black youth through the Black National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice & Sing,” and the tone was set for the show. The Staple Singers were relatively new to Stax, but the band’s legacy was already steeped in years of Black protest tradition, having performed at voter registration drives as far back as the late 1950s. Their stomping take on “Respect Yourself” served as an early show highlight, with Mavis’ distinctive voice leading the group through a soul-stirring “I’ll Take You There” that made the LA Memorial Coliseum feel like a Baptist revival.

Wattstax – I’ll Take You There from Wattstax

Click to load video

The showcase for Stax was more than effective; as audiences got to see the soul, blues, rock, and pop that the label had become known for live. Blues guitarist Albert King delivered standards like “I’ll Play the Blues For You” and “Killing Floor,” alongside Carla Thomas’ effortless throwback pop-soul hits like “Gee Whiz” and “B-A-B-Y.” The Bar-Kays ran through an explosive performance of “Son Of Shaft” and announced themselves as a formidable funk-rock act. Great performances also came from The Temprees, William Bell, Rance Allen, Rufus Thomas, Luther Ingram, and the Newcomers. There was even a gospel singalong of “Old Time Religion,” featuring a host of label artists, led by the likes of Bell and Eddie Floyd.

Because of scheduling issues, there were some notable roster absences. But for those who took the stage, it was a riveting high water mark for the label. The undisputed highlight, however, was Isaac Hayes’ closing performance, which firmly announced the Memphis legend as a cultural icon. Draped in his distinctive gold-link chain vest, with his ever-present bald head and shades, Ike poured himself into stellar performances of “Theme from ‘Shaft’” (originally cut from the subsequent live concert film due to movie copyright), “Soulsville,” and “Never Can Say Goodbye.” These performances both affirmed him as the label’s cornerstone and served as a benediction on Wattstax as a whole; Hayes embodying the new Black consciousness and the effortless cool of Memphis soul. It was a day of Black awareness crystallized in one final set.

The Wattstax Documentary

A concert film/documentary called Wattstax would be released a year after the show, and it serves not only as a document of the performances, but of early 1970s Black life in Watts. Al Bell had recruited filmmakers David Wolper and Mel Stuart for the film, but used a mostly Black film crew to capture both the show and the interviews throughout the community. The doc also features footage of the riots, and humorous running commentary on politics and culture from Richard Pryor, who was on the cusp of wide stardom and in his sociopolitical prime. In 2004, Stuart recalled meeting Richard Pryor before the legendary comedian’s inclusion in the film. “I started talking to him,” Stuart recalled. “And I said to him, ‘Say, what do you think about women? About sex?’ or ‘What do you think about the blues, or gospel?’ Whatever. And he would wind up with a half an hour off the top of his head, out of nowhere. And we used it. It was marvelous.”

The Wattstax documentary is an unfiltered snapshot of the era, with Black voices discussing Black issues with unpretentious, unflinching honesty. It also includes performances from Stax artists who didn’t perform at the actual show, like The Emotions and Johnnie Taylor. Despite the editing challenges with Hayes’ performance, and an R rating that prevented attracting a wide audience, the concert film garnered a Golden Globe nomination for Best Documentary.

The Legacy Of The Wattstax Concert

The Wattstax concert faced some complaints. The police presence at the event was criticized, and community leaders felt the festival had gone from grassroots to crassly commercialized. But the spirit of the event was powerful, and has endured decades after the show itself. It was the second-largest gathering of African Americans at one event at the time, with more than 110,000 people in attendance, second only to 1963’s March On Washington. A total of $73,000 was raised for the Watts community.

“We believed that Wattstax would demonstrate the positive attributes of Black pride and the unique substance found in the lives, living and lifestyle of the African American working class and middle class,” Bell explained in 2004. “While revealing some insight into their internal thoughts during a time when we were still struggling to be recognized, respected, accepted as human beings and to be granted ‘equal rights’ as enjoyed by every other ethnic group in the larger segment of American society.”

In giving voice to the community at a time when it was so eager to speak for itself, Bell and Stax provided a platform for a culture that had been maligned and marginalized in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement. Wattstax is a document, but it’s also a triumph. As so many of the struggles of that period echo today, it’s important to celebrate what this show was, what it meant (and still means), and what it reflects about the Black experience in America.

We are republishing this article to celebrate the anniversary of the Wattstax concert in 1972. Black Music Reframed is an ongoing editorial series on uDiscover Music that seeks to encourage a different lens, a wider lens, a new lens, when considering Black music; one not defined by genre parameters or labels, but by the creators. Sales and charts and firsts and rarities are important. But artists, music, and moments that shape culture aren’t always best-sellers, chart-toppers, or immediate successes. This series, which centers Black writers writing about Black music, takes a new look at music and moments that have previously either been overlooked or not had their stories told with the proper context.