Reggae and Dancehall superstar Buju Banton recently shared his unfiltered views on Reggaetón, accusing professionals in the genre of profiting from Jamaican musical heritage without proper acknowledgment or collaboration with the island’s artists.

On the latest episode of the Drink Champs podcast with hosts N.O.R.E. and DJ EFN, Banton expressed his frustration with the perceived appropriation of Jamaican rhythms and sounds.

“Listen, a lot of culture vultures out there,” he said. “We have sat and we have watched Reggaetón f-ck with our music so hard and stolen our culture.”

“I am not knocking anybody but you don’t give us no respect motherf-ckers, and you still expect us to act like we take something from you? This is the King’s music. Your music shall come and it shall go cause it has nothing to do with soul and building energy. Our music is time marker.”

Later in the interview, Buju reflected on the early days of Reggaetón and the role of Panamanian artists in embracing and building upon Jamaican music. “When I was 16 years old, I remember a song called ‘Tu Pun Pun,’ El General, right? The Panamanians, they show us love. I went there and I met Kafu Banton, who was a next [Panamanian] forerunner. But then, the music went to Puerto Rico and all ‘bout. And all of a sudden, it’s like, you created this sh*t,” he said.

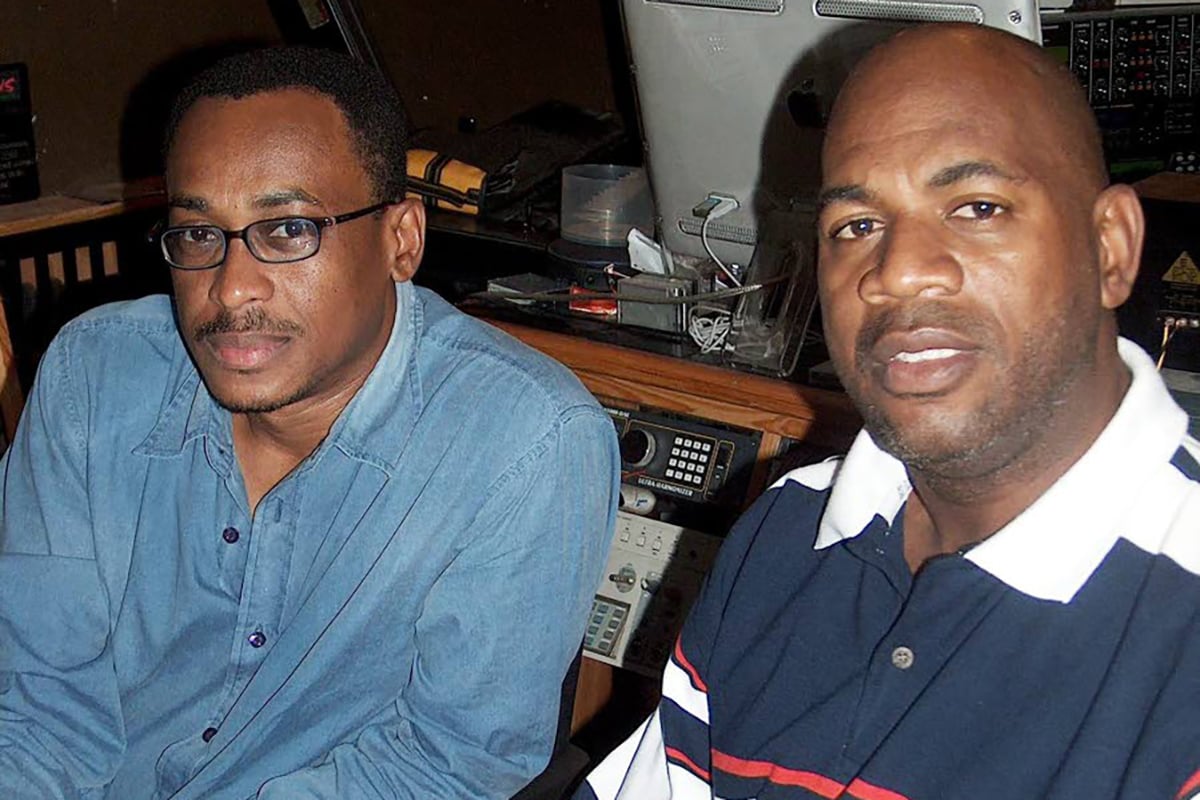

The Champion singer pointed to the ongoing lawsuit filed by Jamaican production company Steely & Clevie against over 160 Reggaetón artists and producers, including Bad Bunny, Pitbull and Daddy Yankee, as evidence of alleged theft and appropriation. Initially filed in a California Federal court in 2021, the case centers on the duo’s “Fish Market” rhythm, better known for its use in Shabba Ranks’ hit Dem Bow, which both sides agree is a foundational element of many Reggaetón tracks.

“Steely & Clevie is one of our biggest producers,” Banton continued. “These guys have been biting this sh*t because they think we’re from the Caribbean and there’s no intellectual property control or we have no idea what we’re doing. But it’s a new day in Gotham. The Batman is still alive.”

Lawyers for the defendants, which include subsidiaries of the major labels UMG, Sony Music, and Warner Records, had tried to have the case thrown out of court, arguing, among other things, that the allegedly stolen portions of the rhythm were too simple and common to be copyrighted.

However, in May of this year, the judge allowed the case lawsuit to proceed to trial, ruling that he couldn’t deem the elements borrowed from Steely & Clevie’s work as ‘commonplace’ just because Reggaetón artists have used them extensively for years. He also noted that the Jamaican company had presented a strong argument for the protectability of the drum pattern and compositional elements, but more evidence and expert testimony was needed so a jury could determine if the copied portions were qualitatively significant.

During the Drink Champs interview, Banton’s criticism extended beyond the legal battle when he questioned the lack of collaboration between Jamaican and Reggaetón artists.

“Did you hear a song with Shabba with El General? no. Buju with El General? no. And you go along the list; the answer is no, no, no. I take Buju out of the equation; name somebody else!” he said.

When someone in the studio mentioned that Sean Paul had collaborated with several Reggaetón artists, including Karol G, Buju quipped: “Well, you know they went to the same karate school.”

He continued: “The reality exists that it’s not present. There’s nothing in the archives, and I’m not talking [about] something frivolous—I’m not capping. Go do your research.”

Brian McBrearty, a US-based musicologist, has warned that a verdict in favor of Steely & Clevie could lead to “tremendous confusion” across genres that heavily rely on rhythm, potentially forcing Reggaetón to “become something pretty new.”

“It also helps to consider that purpose of copyright is to promote creativity. We all want more music. To grant a monopoly over a basic rhythm would do the opposite; it would restrict creativity. So if you’d like more Reggaeton, be careful what you wish for here,” he previously told DancehallMag.

Ewan Simpson, Chairman of the Jamaica Reggae Industry Association (JaRIA), agreed that the case could have far-reaching implications.

He added that the outcome could embolden exploited creators and make the exploiters think twice. “Borrowing has long been part of the development of music, but giving credit and reasonable compensation to creators for their work is equally a pillar of the industry that should be respected,” Simpson said.