John Martyn’s best songs had an intensity and raw emotional power that earned him a cult following which remains strong even today. Martyn was a musical maverick, a bitingly honest songwriter, and one of the most brilliant acoustic guitarists of his generation.

One of Martyn’s biggest technological innovations was his use of Echoplex delay, which allowed him to build layers of guitar. The technique was ahead of its time, and has been cited as an inspiration by U2’s The Edge. As well as influencing contemporaries such as Eric Clapton, Martyn’s work has earned him adoration from artists as varied as Beck, Joe Bonamassa, and Beth Orton. Although Martyn never had a hit single, some of his best songs, including the folk anthem “May You Never” and the ethereal “Solid Air,” are modern classics.

His finest work was for Chris Blackwell’s Island Records, who called Martyn “a true one-take man.” Blackwell gave the musician the time and backing to create a very personal sound. Although Martyn was a powerful live performer, dazzling with his guitar work and his extraordinary smoky, sweet-voiced inflections, he instinctively understood what was needed for music to come alive in a recording studio. As a result, he left a series of enduring albums from a volatile four-decade career.

Listen to the best John Martyn songs on Apple Music and Spotify.

Getting Started

(“May You Never,” “Sweet Little Mystery,” “Fine Lines,” “Don’t Want to Know,” “Couldn’t Love You More”)

As a youngster, Martyn was a fan of the guitar styles of blues men such as Mississippi John Hurt and Skip James. He developed his own hard plucking, dextrous style to accompany his brooding, introspective lyrics. The combination became a trademark of much of Martyn’s best work in the 1970s. His most enduring song is perhaps the catchy “May You Never,” which appeared on the 1973 album Solid Air. Fellow folk guitar maestro Richard Thompson, who played with Martyn in this era, said, “you could put it into a hymn book.” Martyn’s friend and occasional collaborator Clapton covered “May You Never” on his 1977 album Slowhand.

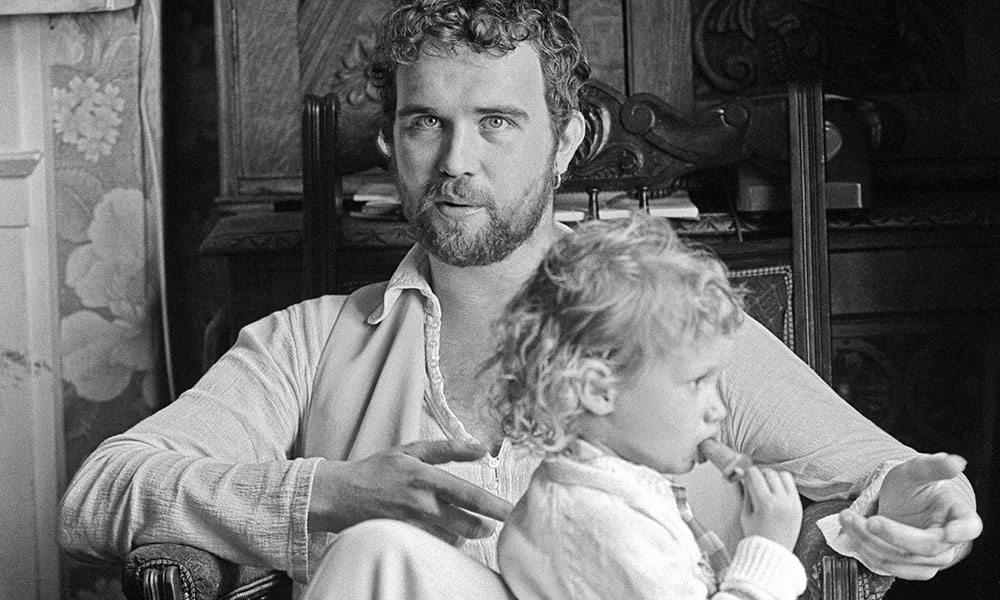

Martyn was born Ian David McGeachy, taking his stage name when he moved from Scotland to London in 1967. He recorded accessible, melodic tunes throughout his career, including “Sweet Little Mystery” from 1980’s Grace and Danger. Martyn oozed ease, something evident on “Fine Lines,” a song which featured his ad-libbed comment that “it felt natural” – an aside retained on 1973’s Inside Out album – as he slid into a tender song about friendship and loneliness. The album was made with “no self-consciousness… probably the purest album I’ve made musically,” said Martyn.

The son of two light opera singers, John Martyn’s best songs often saw him using his voice like an instrument, especially when he was repeating phrases. He sings impressively on “Don’t Want to Know,” also from Solid Air, which was written in Hastings with the help of his first wife Beverley Kutner. Another good introduction to Martyn’s back catalogue is “Couldn’t Love You More,” from 1977’s One World, which featured his long-term collaborator and bass player Danny Thompson. On the surface, it’s a sweet romantic ballad but, in typical Martyn fashion, there is an ambiguous undertow to the tender lyrics, suggesting a lover who has nothing more to give. With Martyn, the darkness usually held back the light.

The Hypnotic Studio Artist

(“Solid Air,” “Go Down Easy,” “Small Hours”)

Martyn was a musician who brought the intensity of a live performance to studio work. “Solid Air,” the mesmerizing title track to his most popular album, was written for his friend Nick Drake, shortly after the release of Drake’s masterpiece Pink Moon. In the years since Drake’s death in November 1974, the song has turned into a kind of requiem for the talented singer-songwriter, who was just 26 when he passed away.

Martyn once told me that he loved jazz saxophone players – he raved in particular about Ben Webster – and the singer’s deftly-phrased delivery gelled magnificently with the tenor saxophone playing of Tony Coe on “Solid Air.” Coe was a sought-after session man who had recorded with jazz greats such as Dizzy Gillespie and Art Farmer. “John Martyn would smooth in his entries like a saxophone. It was almost like an actor’s voice,” John ‘Rabbit’ Bundrick, the keyboard player who performed on the album told Graeme Thomson, author of an excellent biography entitled Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn.

“Go Down Easy” is another song from Solid Air that has an atmospheric appeal. It’s worth listening closely to the way Martyn and upright bass player Thompson interact throughout. Thompson once said that playing with Martyn was like “a natural musical conversation.” The arrangement of the song, which was recorded like a live jam session, allowed Thompson’s deft playing to entwine with Martyn’s guitar playing in what is a masterclass of intonation.

John Martyn’s best songs often had a hypnotic, free-form grace, something evident on One World, the triumphant album he recorded at Chris Blackwell’s house Woolwich Green Farm in the summer of 1977. The project started in Jamaica, involving singer and producer Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, when Blackwell made the rare decision to produce Martyn. He got the best out of the singer. The title track featured a haunting guitar solo, while the epic, soothing “Small Hours,” which is just under nine minutes, is one to let wash over your brain.

Soul-Bearing Master Of Despair

(“Bless the Weather,” “One Day Without You,” “Hurt in Your Heart,” “Our Love,” “Angeline”)

“Bless the Weather” is a fierce love song and a good example of the way Martyn explored the flaws and frailties of the human heart. As his career went on, Martyn’s compositions grew progressively bleaker. The man who wrote the warm-hearted “One Day Without You” (“One day without you/And I feel just like some lost ship at sea”) in 1974 was a different beast to the man who went into the studio six years later to record Grace and Danger. By that point, Martyn was trying to make sense of “a dark period in my life,” one that included divorce and addiction.

The pain came out in eviscerating confessional songs such as “Hurt in Your Heart” and “Our Love.” Martyn is quoted in Thomson’s book as saying that the songs on Grace and Danger were “probably the most specific piece of autobiography I’ve written. Some people keep diaries, I make records.”

Although Grace and Danger marked the last true high point of Martyn’s album-making, he returned to the theme of lost love with “Angeline,” on 1986’s Piece by Piece. Although “Angeline” is a more melodic offering than “Hurt in Your Heart,” it is full of passion and sorrow. Island released it as a single, but it’s worth seeking out live versions, where Martyn extended the song considerably.

The Fun Side Of A Complex Man

(“Over the Hill,” “Dancing,” “Singin’ in the Rain”)

Although some of John Martyn’s best songs have a mordant, disturbing quality, he was also a witty stage performer, capable of recording exuberant, joyful songs. The acclaimed comedian Billy Connolly, who was a folk singer himself in the mid-1960s in Scotland, remembered Martyn as “a good laugh.”

One of Martyn’s most uplifting songs is “Over the Hill,” from Solid Air, on which Richard Thompson plays mandolin. Martyn’s song, which describes a homecoming, was written about the final part of a journey into Hastings, the train ambling through the countryside before revealing the seaside town.

Island released his 1977 song “Dancing” as a single, and this Afrobeat paean to the joys of the life of a traveling, stay-out musician, is truly infectious. Martyn was never enamored with the old-fashioned image of British folk music – which he scornfully dismissed as “the dingly-dangly-dell of life” – but he was a fan of nostalgic songs that put “a smile on your face.” He frequently performed “Singin’ in the Rain,” both live – where he encouraged singalongs – and in the studio, including his 1971 version on Bless the Weather.

The Covers

(“Wining Boy Blues,” “The Glory of Love,” “I’d Rather Be the Devil,” “Spencer the Rover”)

Martyn was a gifted interpreter. He even cut a whole album of covers – 1998’s The Church with One Bell – which featured songs written by Randy Newman, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Elmore James, and Bobby Charles. Martyn grew up loving Jelly Roll Morton’s “Wining Boy Blues” and he recorded his own version early in his career, along with a touching take on Billy Hill’s “The Glory of Love,” a song first made famous by Benny Goodman in the 1930s.

One of his most spell-binding performances was of Skip James’s “Devil Take My Woman,” which Martyn retitled “I’d Rather Be the Devil” for Solid Air and turned into a passionate six-minute tour-de-force, full of the electronic effects from the tape device known as the Echoplex. Although Martyn had originally played straight acoustic versions of the song – which he’d learned at Les Cousins Folk Club in London in 1969 – his recorded version was the finest example of his experiments with Echoplex, something that started with the 1970 album Stormbringer! By 1973’s Solid Air, it had become a key part of his repertoire, his skill with it even earning praise from Bob Marley. “Bob was totally blown away,” Blackwell is quoted as saying in Thomson’s book.

Although Martyn rarely covered traditional songs, his version of “Spencer the Rover,” a folk song that had origins in the northern English county of Yorkshire, is sublime. Martyn, who named one of his sons Spenser, always enjoyed singing what was, perhaps, a romanticized version of his own wild wanderings.

Martyn’s roving days came to an end in 2003, when he had his right leg amputated below the knee because of a burst cyst. He continued performing until 2008, using a wheelchair. When Martyn received a lifetime achievement award at the 2008 BBC Folk Awards, Clapton was quoted as saying that the innovative Martyn was, “so far ahead of everything, it’s almost inconceivable.”

Think we’ve missed one of the best John Martyn songs? Let us know in the comments section below.