B.B. King was the undisputed King of the Blues. Part of this was down to his incredible work ethic. Even in his final years, he was still performing 100 concerts a year with his famous guitar he named Lucille. In playing so many shows and continuing to release albums, he introduced people to the music he loved and made people realize that the blues could make you happy, just as easily as they can make you sad.

Riley B. King was born in Indianola, deep in the Mississippi Delta, in 1925. He was the son of Alfred King and Nora Ella King. He was named Riley after the Irishman who owned the plantation on which his parents lived and worked. “My dad and Mr. O’Riley were such good friends,” B.B. remembered, “he named me after him, but he left the O off. When I got big enough to know about it, I asked my dad one day, ‘why is it that you named me after Mr. O’Riley, why did you leave the O off?’ He said you didn’t look Irish enough!”

According to B.B. King, “Any time you’re born on a plantation you have no choice. Plantation first, that’s always first.“ But it was not long before The Beale Street Blues Boy, as Riley B. King became known, sought to change all that. The sharecropper’s son first went to Memphis in 1946 and stayed with his cousin Bukka White, but soon returned to Indianola to work as a tractor driver. “My salary, which was the basic salary for us tractor drivers, [was] $22 and a half a week. [That] was a lot of money compared to the other people that was working there,” explained King.

But music was calling. King had already been singing and playing guitar for many years by that point. Inspired by Sonny Boy Williamson’s radio show, young Riley moved back to Memphis in 1948.

One of his first guitar teachers during this time period was Blues legend Robert Lockwood. In Robert Palmer’s Deep Blues, Lockwood claims that King’s “time was apesh-t. I had a hard time trying to teach him.” Nonetheless, King “got to audition for Sonny Boy, it was one of the Ivory Joe Hunter songs called ‘Blues of Sunrise.’ Sonny Boy had been working out a little place called the 16th Street Grill down in West Memphis. So he asked the lady that he had been working for, her name was Miss Annie, ‘I’m going to send him down in my place tonight.’ My job was to play for the young people that didn’t gamble. The 16th Street Grill had a gambling place in the back, if a guy came and brought his girlfriend or his wife that didn’t gamble my job was to keep them happy by playing music for them to dance. They seemed to enjoy me playing, so Miss Annie said, ‘if you can get a job on the radio like Sonny Boy, I’ll give you this job and I’ll pay you $12 and a half a night. And I’ll give you six days of work, room and board.’ Man, I couldn’t believe it.”

B.B. King – Thrill Is Gone (Live)

Click to load video

King soon began working at WDIA, a local radio station. “When I was a disc jockey, they use to bill me as Blues Boy, the boy from Beale Street. People would write me and instead of saying the Blues Boy, they’d just abbreviate it to B.B.” His popularity in Memphis earned him the chance to record for Bullet in 1949. His first sides weren’t particularly successful, but then Sam Phillips got B.B. into his Memphis Recording Services studio in September 1950.

The start of the most successful long-running career in blues history

At the time, RPM Records’ Bahiri brothers were visiting Memphis in search of talent, and agreed to release the sides that King had cut with Phillips. These records failed to catch hold and so Joe Bihari, the youngest brother, went to Memphis and recorded B.B. in a room at the YMCA on January 8, 1951. On a subsequent visit to Memphis, Bihari recorded B.B.’s version of Lowell Fulson’s “Three O’Clock Blues.” It entered the chart on December 29, 1951 and eventually spent five weeks at No.1 in early 1952. Not quite an overnight sensation, but it was the start of the most successful long-running career in modern blues history.

In the early years of his success, King stayed in Memphis where he was a big star… but he wasn’t always the biggest star on every stage. “We were in Memphis at the Auditorium, Elvis was there watching,” King remembered. “Performing were Bobby Bland, Little Milton, Little Junior Parker, Howlin’ Wolf and myself. Everybody had been on stage. Bobby Bland, a stage mover man, he can move the people, Little Milton and myself, you know we do what we do, but we couldn’t move the crowd quickly like Bobby Bland. We had been on and now Howlin’ Wolf is up and the people are going crazy. Milton says, ‘Something is going on out there.’ Junior Parker says, ‘Let’s check it out.’ So Wolf is doing ‘Spoonful,’ now we go out there and he’s on his knees crawling round on the floor. The people just going crazy, so finally we figured out what it was; the seat of his pants was busted! And all of his business is hanging out!”

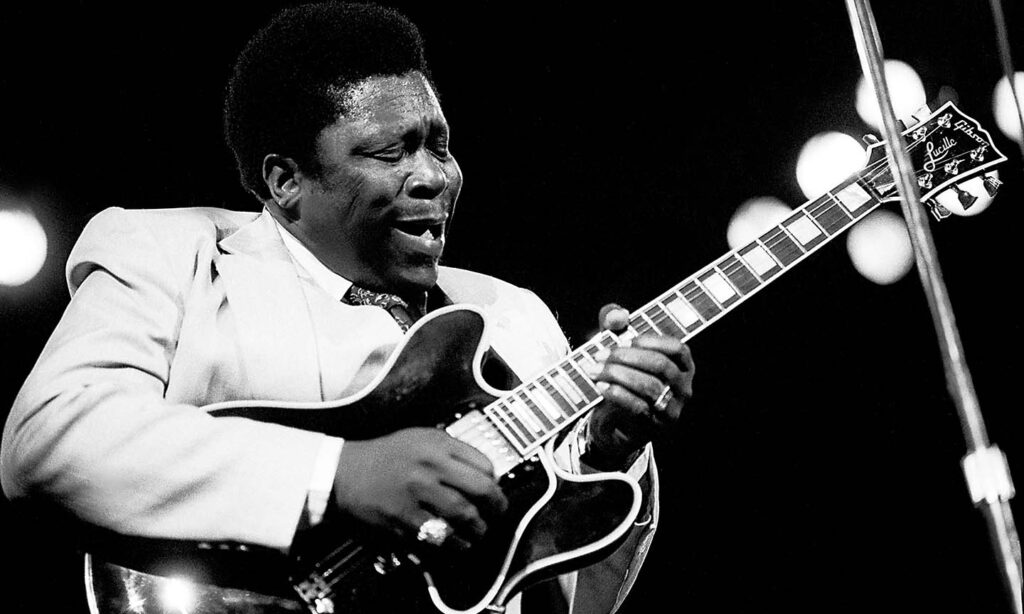

The origin of Lucille

One night while B.B. was playing at a club in Twist Arkansas, there was a fight and a stove was knocked over which set fire to the wooden building. The band and audience rushed outside before King realized that he had left his beloved $30 guitar inside. Rushing back into the burning building, he managed to get his guitar – even though he almost died in the process. The fight in the club? It was all over a woman named Lucille, which is how B.B.’s guitar got its name. Every one of the 20 or so custom-made Gibson guitars that King played during this career were called Lucille.

B.B King – Live in Stockholm 1974

Click to load video

Throughout the time King recorded for RPM, he churned out hit after hit, topping the R&B chart three more times. He left RPM for Kent in late 1958, a stop that lasted throughout much of the 60s. While he never again topped the R&B charts, he had plenty of hits. His sweet gospel-tinged voice coupled with his brilliant single string picking proved an irresistible combination.

“I’m trying to get people to see that we are our brother’s keeper; red, white, black, brown or yellow, rich or poor, we all have the blues.” – B.B. King

Discovered by the young rock fraternity

By the late 1960s King, like many of his fellow blues guitar players, was “discovered” by the young white rock fraternity. It gave his commercial career a real boost. In 1970, “The Thrill is Gone” made No.3 on the R&B chart. It also crossed over to the Hot 100 and became his biggest hit when it made No.15. In 1969 he visited Europe for the first of many visits; audiences, well aware of the legend’s influence on Eric Clapton, Peter Green, et al., readily accepted him. A good portion of that esteem was based on King’s album Live At The Regal, recorded in 1964. “Well B.B. was like a hero,” explained Mick Fleetwood. “The band? You listen to the way that band swings on Live at The Regal, it’s just like a steam roller.”

Much of King’s success can be attributed to his live shows. He was one of the hardest working live performers, playing 250 – 300 dates a year, even in some of his lean years. He also had a knack for keeping his bands together. “The guys are not only great musicians, they’re loyal to me, I’m loyal to them, and we get together and have a good time,” King said in 2000. “Everybody’s been with me a long time, my late drummer, Sonny Freeman was with me around 18 years and now my senior trumpeter has been with me 21 years and everybody, except one, has been with me more than 10 years.”

In 1969 King toured America with the Rolling Stones. According to Bill Wyman, “We used to go on side stage and watch B.B. play. He had a 12-piece band and they were brilliant musicians. The thing that always stunned me about his playing was the way he hammered it out and then he’d just go down to a whisper. There was just silence in the place, you could hear a pin drop. He would suddenly start to build it to a big climax, that’s what I liked about his playing, the dimensions of his music.”

The elder statesman of the blues

In 1988, the year after he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, King worked with U2 on their album Rattle & Hum. His performance on “When Love Comes to Town” proved he still had it, even at 63 years old. This wasn’t the first time King had played with others. Notable collaborations include The Crusaders, Diane Schuur, Alexis Korner, Stevie Winwood, and Bobby Bland. In 2001, King and Eric Clapton won a Grammy award for the album Riding With The King.

Perhaps one of his finest albums, however, was a tribute record. Like many of his contemporaries, King was inspired by Louis Jordan. For many years, King spoke of wanting to record an album of the legendary bandleader’s material. In 1999, he finally did, acknowledging his debt to Louis and celebrating the “King of the Jukeboxes.” The album’s title, appropriately, was Let the Good Times Roll, a song which King used to open his live shows for decades.

The legacy of B.B. King

B.B. King’s great skill was to bring the blues out of the margins and into the mainstream of American music. He took the music he heard as a kid, mixed it and matched it with a bewildering variety of other styles, and eventually helped bring the blues into the digital age. His legacy will loom large over music for years to come.

Looking for more? Discover how ‘Live At The Regal’ took B.B. King from Beale Street blues boy to global legend.